SevenSenses strongly believes that Participatory Action Research (PAR) increases the quality of development cooperation worldwide. PAR adapts to any local situation, empowering communities to tackle their most pressing issues ‘community up’. Let us show you the five most significant differences between traditional forms of top-down development cooperation and Participatory Action Research in development cooperation.

Dependence vs Independence

Top-down development cooperation often creates dependency by providing ‘help’. As soon as it is gone, the situation returns to how it was before. De Beer and Swanepoel (2000) speak of an ‘equilibrium’ of poverty. A top-down developed intervention tackling poverty may lead to some improvement but over time, always returns to that equilibrium. The reason is according to De Beer and Swanepoel that the intervention did not take other important factors into account, which backfires its effects. For example, a brand new water system may have been built, providing people with clean drinking water. This leads to fewer illnesses due to poor hygiene, fewer days lost of work or school, leading to an increased income. But when the system breaks and there are no technicians to fix it, people return to using contaminated water. The rest is history. Such a form of top-down help kills creativity as people are ‘waiting’ until the next help arrives. As Amutabi (2006) noted, it erodes any potential local people may have in efforts at self-development. No wonder people wait until new help arrives if outsiders keep giving the impression they cannot help themselves.

Creating independence with PAR

Through its extensive focus on the local social-cultural context of an issue, PAR opens up the opportunities to lay bare other factors that may form a barrier to making use of a newly created intervention. Moreover, it creates a playground for creativity, (international) connectedness and the co-creation of the best-fitted innovations by the beneficiaries and other stakeholders themselves. It puts people in a cooperative mindset of ‘let’s look at what we can do’. PAR often leads to solutions which people ‘from the top’ would never have thought of and costs often the slightest fraction of the funds. As such, PAR empowers people instead of creating dependency on foreign aid.

Focus on donor’s demand vs focus on local stakeholders’ demand

Here we are talking about the bling bling. The dirty thing about money is that whoever has it, gets to have the power. Especially in the poorer countries -where some of the richest people live- it is always this rich elite who gets the most influence in politics, leading to policies that mostly benefit them rather than their poorer country mates. In the (traditional) developing cooperation realm it is no different. A donating agency has determined goals it needs to achieve during its establishment. So, whether local people need it or not, such an agency needs to reach its goals! This is how there is so often a discrepancy between what donating agencies want and what local stakeholders need. Local NGO’s however often agree with these international ‘big ones’ as it is for them another project they can do, where money comes in. Nowadays, NGO’s are paying more and more attention to ‘the actual demand’, but still, they would only fund the project if it fits with their own policy and goals.

Here we are talking about the bling bling. The dirty thing about money is that whoever has it, gets to have the power. Especially in the poorer countries -where some of the richest people live- it is always this rich elite who gets the most influence in politics, leading to policies that mostly benefit them rather than their poorer country mates. In the (traditional) developing cooperation realm it is no different. A donating agency has determined goals it needs to achieve during its establishment. So, whether local people need it or not, such an agency needs to reach its goals! This is how there is so often a discrepancy between what donating agencies want and what local stakeholders need. Local NGO’s however often agree with these international ‘big ones’ as it is for them another project they can do, where money comes in. Nowadays, NGO’s are paying more and more attention to ‘the actual demand’, but still, they would only fund the project if it fits with their own policy and goals.

Focusing on local stakeholders’ demand with PAR

PAR lets the local people/stakeholders decide and take the lead. When people can decide for themselves what is improving their livelihood they will see the value of the (read: their) project and make it a success. As such, PAR is the complete opposite world of traditional top-down development cooperation. What would happen if people all over the world -with all their manpower and possibilities in their communities- would be able to create and implement their own development projects?

Clear data vs change-data

Many -mostly the bigger- NGO’s implement solutions based on scientific research. They either conduct research themselves or they use scientific literature to back up their policies. For example, randomized controlled trials compare a certain intervention in one community to the ‘placebo’ group. Researchers try to control for as many ‘external factors’ as possible, in order to get ‘clear data’. However, real-life situations have to deal with many context-specific external factors. so, it is impossible to mimic that real life situation and generalize it to other contexts. When NGOs base their decisions and policies on these outcomes, it often leads to project failure as the context of their real-life situation was totally different from the randomized controlled trial. Also when NGO practitioners conduct a needs assessment, they often bind themselves to the strict scientific rules of providing ‘clear data’: any change in that situation over time is considered as ‘blurring their data’. The more the ‘status quo’ is maintained, the less ‘bias’ and the ‘better’ their research results.

Many -mostly the bigger- NGO’s implement solutions based on scientific research. They either conduct research themselves or they use scientific literature to back up their policies. For example, randomized controlled trials compare a certain intervention in one community to the ‘placebo’ group. Researchers try to control for as many ‘external factors’ as possible, in order to get ‘clear data’. However, real-life situations have to deal with many context-specific external factors. so, it is impossible to mimic that real life situation and generalize it to other contexts. When NGOs base their decisions and policies on these outcomes, it often leads to project failure as the context of their real-life situation was totally different from the randomized controlled trial. Also when NGO practitioners conduct a needs assessment, they often bind themselves to the strict scientific rules of providing ‘clear data’: any change in that situation over time is considered as ‘blurring their data’. The more the ‘status quo’ is maintained, the less ‘bias’ and the ‘better’ their research results.

Creating change-data with PAR

Participatory Action Research does not favor ‘clear data’, yet rather assesses ‘change data’. As Cornwall and Jewkes (1995) put it, “Such approaches [PAR] often emphasize generating “knowledge for action” as opposed to just “knowledge for understanding”. First of all, all stakeholders are taken along in the research process and they are the ones co-creating the interventions needed at that time, in their social-cultural context, for the issue addressed. Although the current situation is being mapped out through a needs assessment as well, it is not the end result. Rather, it forms the base for the co-creation of the solution. Implementation of that solution is part of the PAR process and after its implementation, through an iterative process of action and reflection, changes are being assessed (and the project or solution is adapted where necessary). In that sense, PAR favors change data over clear data in order to create sustainable impact.

Funding wasted vs efficiency

Especially after the first time I came into contact with PAR in Guatemala, I started paying attention to development projects throughout my work in developing countries. In the field of top-down led projects, I saw practitioners had to deal with trying to solve upcoming issues after its implementation. For example, after implementation, locals are not motivated to join the programme, leaving practitioners desperate.

Especially after the first time I came into contact with PAR in Guatemala, I started paying attention to development projects throughout my work in developing countries. In the field of top-down led projects, I saw practitioners had to deal with trying to solve upcoming issues after its implementation. For example, after implementation, locals are not motivated to join the programme, leaving practitioners desperate.

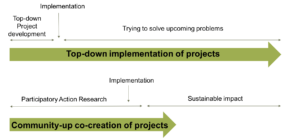

Taking the horizontal arrow in the figure above as ‘time’, you see that the project design of top-down led projects goes pretty fast. It is easy to formulate a goal, milestones and activities if you don’t have to take into account local perspectives. Also the implementation of those projects is mostly fairly easy. However, after it’s implementation, practitioners often encounter problem after problem and need extra funding to solve those problems. For example, practitioners have to organize extra activities to convince the target group -i.e. the supposed beneficiaries of the project- to join or make use of the project, broken materials needed to be fixed et cetera, taking up a huge amount of time, costs and efforts to try to ‘save’ the project.

Creating efficiency with PAR

In PAR, practitioners work directly together with people, what I call community-up, thereby including all stakeholders. The PAR process itself may take up more time -the bottom arrow, but after implementation you may find local people picking up the project based on their own intrinsic motivation as they were the co-creators of it; people solve any problems -if at all they arise- at location, resulting in sustainable impact. As such, more investment in the PAR process -in the end- means cost-efficiency in the long run.

Another money saver is that PAR projects do not need to pass through big organizations or government institutions. It happens on the ground which reduces the chances for corruption enormously. Moreover, solutions that local stakeholders design on-the-ground are first of all often cheaper than solutions that‘the ivory tower’ designs. Last, local stakeholders execute only the activities that they consider meaningful. Working from this intrinsic motivation of all stakeholders, in a way that suits them increases efficiency enormously.

Problem thinking vs strengths-thinking

Traditional top-down development cooperation focuses on ‘what is going wrong’, creating an atmosphere of problem-thinking. According to the social constructionist theory, focusing on problems creates more problems. Western solutions should fix these problems, because ‘there development was successful’. In other words, practitioners often forget about local assets of a community, such as manpower, resources and talents.

Focus on strenghts-thinking with PAR

After unraveling the problem as perceived by local stakeholders, PAR puts emphasis on strengths, such as ‘what is going well’, ‘what are past successes where people are proud of, ‘what is in abundance’ ‘what talents are present in the community’ et cetera. With this, PAR creates a positive atmosphere in which people see more and more opportunities for improving their livelihoods.

After unraveling the problem as perceived by local stakeholders, PAR puts emphasis on strengths, such as ‘what is going well’, ‘what are past successes where people are proud of, ‘what is in abundance’ ‘what talents are present in the community’ et cetera. With this, PAR creates a positive atmosphere in which people see more and more opportunities for improving their livelihoods.

Towards worldwide empowerment of people

What I have written here may be a bit ‘blunt’ or ‘black and white’; there are numerous NGOs who do awesome things for communities. They increasingly take local perspectives into account, do not take things for granted anymore and learn from past mistakes (their own or other’s). There is a great shift going on worldwide where development cooperation becomes more and more effective and efficient. Yet we still have lots to improve. I strongly believe PAR can accelerate that shift towards effective, efficient and sustainable development cooperation.

References

De Beer, F., Swanepoel, H. (2000). Introduction to development studies. Oxfort University Press Southern Africa.

Amutabi, M. N. (2006). The NGO Factor in Africa: The Case of Arrested Development in Kenya (African Studies) (1st ed.). Routledge.